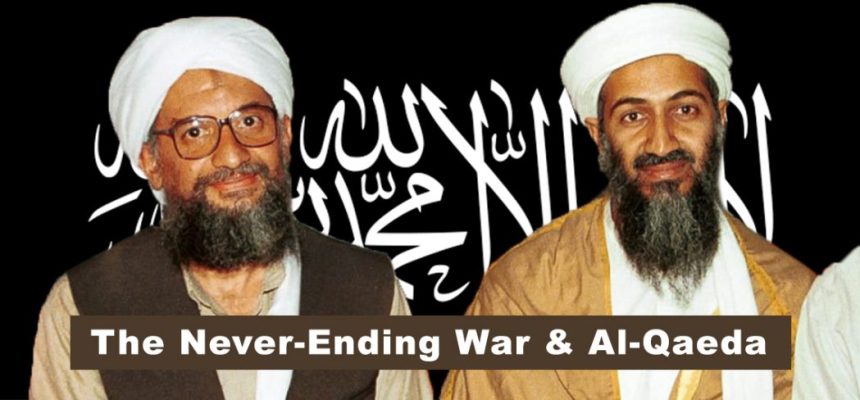

Long in hiding, Ayman al-Zawahiri, the commander of Al-Qaeda, was killed on July 31 in the early hours by a targeted drone attack in Kabul. As expected, the strike has been the subject of a rush of media coverage and analysis.

Views vary depending on which of the three main topics is emphasised: (1) counter-terrorism capabilities, particularly over-the-horizon capabilities; (2) ongoing intelligence work that enables and supports CT ops; and (3) the employment of cutting-edge technology tools to carry out operations.

As Vice President, Biden consistently opposed counterinsurgency strategies that cast a wide net and included funding for Afghan civil society, training and equipping of the Afghan National Security Forces, and budgetary support for Afghan governments after the invasion. This is a matter of public record and has been extensively discussed by Steve Coll and others.

As a result of the withdrawal of US forces from Afghanistan, Biden is now free to concentrate on over-the-horizon CT operations. Al-assassination Zawahiri is a prime example of one of these operations. In addition to receiving the majority of support from the Beltway policy wonks, it also fits with Biden’s domestic political obligations. When you locate terrorists, you kill them.

The US does receive a perfect score if one limits its analysis to top-notch intelligence work and the application of cutting-edge technology tools to track, find, identify, and execute al-Zawahiri. The strike appears even more audacious when combined with some evidence that the operation may have received ground backup or that the US had forces on the ground in a hostile city.

Simply, the action was planned and carried out successfully from a tactical and operational standpoint. The research conducted by Nelly Lahoud in her book The Bin Laden Papers, which is based on the collection of papers and digital data that the US Navy SEALS carried away after killing Bin Laden, supports the employment of drones and their tactical and operational efficacy.

The drones were successful, which significantly reduced al-Qaeda cadres. The operational genius of the strike aside, there are murkier worlds beyond the tactical. And this is when the bigger picture enters the scene.

Also Read: Taliban say ‘no information’ about Al Qaeda chief Zawahiri in Afghanistan

No longer in question, America’s Forever War has failed to achieve its political-strategic goals in Afghanistan, Iraq, Libya, or Syria.

Both Al-Qaeda and the Taliban have returned to Afghanistan. In addition to operating in Afghanistan, the ISK is launching assaults in Pakistan. Afghanistan is the base of operations for the banned terrorist organisation Tehrik-e-Taliban Pakistan.

Iraq’s economy is in bad health, and unemployment is still high despite its fortune in oil. It lacks a president and has polarising politics, with several organisations operating nearly in parallel with the government. At the time of writing, a stalemate between rivals of Shi’ite cleric Moqtada al-Sadr and supporters of Iran is still going on.

Since the 2011 Arab spring, two civil conflicts have ravaged Libya. Foreign interference has exacerbated the conflict, giving rise to several armed competing factions and causing a severe humanitarian catastrophe. The same is true of Syria.

This is the result of both direct US actions as well as indirect backing for particular organisations employing special operations and capabilities from over the horizon.

Therefore, the question is whether the US’s highly outstanding CT capabilities address more complex issues than just short-term tactical and operational triumphs.

Again, the consensus is that the answer is no. According to Spencer Ackerman’s 2021 book Reign of Terror, “constant conflict” would “become self-defeating and transform our society in worrisome ways.” Obama’s failure to use this information to inform his decisions during his term is a huge tragedy.

Even after [the] myth died in Iraq, the fallback position among the politically strong [in the US] was that extrication was more hazardous than a quagmire,” continues Ackerman. In the long run, a constrained, controlled quagmire may even be consistent with America’s wider hegemonic posture of ongoing overseas operations carried out in the name of the “rules-based international order.”

Also Read: Al Qaeda leader Zawahiri killed in US drone strike in Afghanistan: Biden

Of course, Ackerman is a ferocious opponent of America’s Forever War, and his views on the US, its place in the world, and its endless conflicts are not exactly those of Beltway specialists and the American security establishment. To determine if the US has been successful in achieving its political-strategic goals, it may be preferable to locate someone from the US hard-line establishment. Please give Herbert Raymond McMaster, a former US Army Lieutenant General and US National Security Advisor, a warm welcome.

According to McMaster, Trump should remain in Afghanistan. As a result, many of his assumptions about what the US might do in that country after the war is over can be challenged. Few in the [US] military took the time to consider how McMaster’s plan to suppress the Taliban would work until the unlikely day when they would disprove it, according to Ackerman.

Nevertheless, McMaster delivered some incisive remarks regarding America’s disregard for the political and humanitarian aspects of conflicts in 2014 when speaking at The Defence Entrepreneurs Forum. He named four of them: the RSVP fallacy, the Mutual of Omaha fallacy, the Zero Dark Thirty fallacy, and the Vampire fallacy.

According to McMaster, the vampire fallacy “is the belief that a limited range of technological capabilities will deliver fast, cheap, and effective victory in future war(s).” The conviction in a wide variety of new technology capabilities, including big data analytics, artificial intelligence, drones, robots, and other things, is the most recent incarnation. It is hard to kill this delusion, like a vampire… It reappears nearly every decade.

The Vampire fallacy is similar to the Zero Dark Thirty fallacy, which alludes to the 2012 movie about finding and killing Bin Laden. It elevates raiding, a crucial military capability, to the status of a defence strategy. As opposed to being a supplement to traditional Joint Force capabilities, the US capacity to undertake operations against networked terrorist organisations is depicted as a replacement for them. This alludes to the numerous night raids the US Special Forces carried out in Afghanistan and Iraq.

“The problem with both these fallacies is [that] they represent important capabilities you need to have, but these are masquerade[d] as strategies and simple solutions to the complex problem of war, neglecting war’s political nature, war’s human nature, [and its] uncertainty based on the interactive nature, and finally neglecting that it is ultimately a contest of wills,” McMaster said to Allison Schrager at Quartz.

There were two US television shows from the 1960s that are mentioned in the Mutual of Omaha Wild Kingdom fallacy. According to the Mutual of Omaha Wild Kingdom fallacy, the US uses proxies to carry out land battles. Although it is difficult to foresee future operations where US troops would not work with various partners, relying heavily on proxies is frequently problematic owing to concerns surrounding capabilities and the desire to engage in a way that serves US goals.

The RSVP fallacy concludes with the statement, “Thank you for the kind invitation to the war, but the United States regrets it is unable to attend.” “This is the assumption that you can just opt out of war,” he explained to Schrager. “It’s a narcissistic attitude to war [in] which we define conflict as just about us and what we’d want to accomplish.”

The reader may observe that McMaster does not express a direct objection to the concept of America’s Forever War. Additionally, he has little interest in the legitimacy of US decisions to declare war or Jus ad Bellum. He is not contesting the human suffering brought on by such operations in Iraq and Afghanistan or the legitimacy of targeted and signature drone attacks when he refers to the Vampire and Zero Dark Thirty fallacies. Instead, he is emphasising how such skills cannot replace the inherent complexity of the conflict. But his diagnosis is fairly illuminating when seen from a strictly operational perspective.

This gets us back to the al-targeted Zawahiri’s killing: Will it weaken AQ (which has affiliates in many regions of the world currently) and will the killing itself address the issue of “terrorism” as it is understood by the US? Without the purpose of ending the War on Terror, the administration [has] failed, as did its three predecessors, to explain exactly what executing someone as Zawahiri accomplishes,” wrote Ackerman on August 1, a day after al-death.

This is a crucial topic, not so much in terms of the necessity to kill al-Zawahiri, who may have been betrayed by a Taliban party, but rather in terms of whether such targeted killings would succeed in ending the Forever War as a whole.