For over forty years Afghanistan has been embroiled in war and now with the climate hazards becoming more evident, added with risks posed by the coronavirus pandemic, hundreds and thousands of people suffer this fate.

The world wants the Taliban-led interim government to deliver, but to deliver on empty pockets and decaying resources is an unreasonable demand. The humanitarian crisis has deepened ever since global financial institutions like the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank (WB) cut off aid flows; The United States (US) has shown no signal to unfreeze massive Afghan funds while the situation continues to worsen.

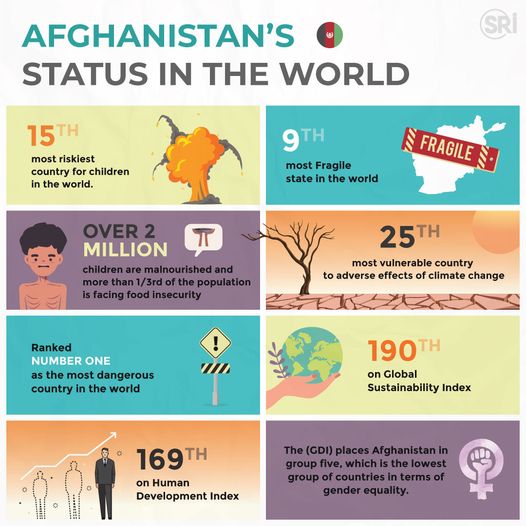

According to the fragile state index, Afghanistan stands at the 9th position with the state nearly becoming dysfunctional and paralysed, and it is the 5th most at-risk country on the natural hazard risk index 2019. From 1950 to 2010 Afghanistan’s temperatures have increased twice the global average, up to 1.8 degrees celsius, despite its meagre contribution to carbon emissions. Rainfall is sparse with droughts leaving millions of people at risk of starvation and more occurrences of internally displaced Afghans. In The New York Times, Somini Sengupta quoted Noor Ahmad Akhundzadah, a professor at Kabul University saying, “The war has exacerbated climate change impacts. For 10 years, over 50 per cent of the national budget goes to the war.”

A Costly Conflict

What started as an operation to hunt down one man, turned into 20 years of thousands of innocent Afghans dying along with it. Brown University’s cost of war project has shared that up to 241000 people have died since the September 11 attacks. About 66000 Afghan military and policemen lost their lives while more than 2.7 million of the 38 million Afghan population fled to neighbouring states to protect themselves from war. With the Taliban under control of a decrepit country, more immediate challenges await.

The country is suffering from a severe “brain drain”. Most people with technical know-how have abandoned their own land first to avoid war, and now to escape the Taliban’s rule. The economy is in disarray with about 90 per cent of the people sinking below the poverty line and with no safety net to secure jobs for many people. Estimates suggest that the GDP is down by 30 per cent, banks are unable to function, and the education sector is looking grim as well. The U.S. Federal Reserve has “frozen” some $7 billion reserves under the pretext that the Taliban will misuse this sum. What it has done is that Afghanistan’s central banks can no longer sustain their currency, leading to hyperinflation and its exchange rate plummeting.

Another aspect that requires serious attention is the state of health and especially mental health. Afghanistan has been labelled as a ‘trauma state’ due to the constant exposure of violence and explosions. For the Afghan population to ‘normalise’ might itself take decades as there has been a clear rise in post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), anxiety disorders, depression and stress, etc linked to armed conflict. International Psychosocial Organisation (IPSO) estimated that 70% of Afghanistan’s 37 million people are in need of psychological support. These issues are further exacerbated in children who may live with lasting impacts on their lives, as currently there are no such facilities available.

Afghanistan’s Climatic Tragedy

Conflict coupled with climate change, and an empty treasury with zero institutional capacity is leading towards a massive adversarial impact. Reports have suggested that Afghanistan is becoming more and more water-scarce. The country has several rivers and all are affiliated with a myriad of problems ranging from regional to social ones. The Helmand River basin in particular is more vulnerable. The traditional water systems are at a greater risk as well, for example, the ‘karez’ systems have dried up over the last two decades and the country is likely to see extreme water reduction due to its increasing temperatures, which also poses a major threat to the glacial mass in the Emirate.

These issues directly impact the agricultural sector, upon which more than half of the population is dependent. Reports indicate that the indigenous people face natural disasters almost regularly. A case as such is from 1997-2007 that showed a 50 per cent cut in livestock due to the persisting droughts. These dry spells can be damaging to agricultural production creating a scarcity of agricultural land and conditions for food insecurity. Up to 80 per cent of the population is affected due to lack of rain, as the locals survive on rain-fed farming. The constant fighting has tampered with crops plantation; the World Food Program (WFP) shared that 40 per cent of crops have been reduced and the cost of wheat has risen by 25 per cent. Many aid agencies are running out of their own food stock to meet growing demands. Climate change will also significantly damage food production; The alterations in soil, precipitation, temperature, pests and disease outbreaks will influence food production via direct and indirect effects on crop growth.

The World Food Program has reported that child malnutrition globally could rise by 20% by the 2050s. Meanwhile, more than 40.8 climate-induced deaths per million population are expected by the 2050s in Afghanistan alone; Scientists have shared that the chances of heat-related deaths are also becoming more and more potent. Unfortunately, these conditions directly create a health crisis with no state of the art infrastructure and manpower to rely on except for the NGOs operating.

The water issues can cause an unprecedented energy crisis in a country that is already unable to meet its current demands. While Afghanistan has the potential to thrive on solar and wind energy generation, (studies showed that either one of those renewable sources can produce energy that exceeds the country’s total projected power demand in 2032), the constant conflict has disrupted the country’s capability to deliver and this includes issues like corruption and politics as well.

Much of the climate change projection is already affecting the poor and those in the rural areas. Before the pandemic hit, about 54 per cent of the population was living below the poverty line, however current estimates suggest that this has likely changed to 72 per cent of the population.

From big summits to empowering locals, where does the International community stand?

For many Afghans and members of the international community, it is still a hard pill to swallow that the Afghan Taliban are the leading faction of Afghanistan now. While neighbouring countries like Pakistan and China have been aiding the country, this adhocism will not bring the required stability to the region. The Climate Summit is expected in the coming weeks in Glasgow, so any discussion there is likely to have implications for the country. This is where the world can utilise “environmental peacebuilding” to keep the country and the Taliban engaged, and perhaps develop a level of trust between multiple parties by helping thousands to survive.

Jost Pachaly told DW, “They will not be able to run the country without assistance, they must know this…It’s a very critical question for the international community: how to deal with the situation — not to support the Taliban but also not let the Afghan people suffer … This is a humanitarian disaster.” A member from the Taliban’s cultural commission mentioned to Newsweek that without collective efforts, there is no solution to these problems.

It is understandable why the international community is delaying global recognition, but climate hazards will not wait for the international community’s readiness to welcome the new leaders of Afghanistan. The world, especially the regional countries will have to come up with targeted projects to cope with climate change in Afghanistan. It serves in the favour of all countries to avoid the spillage of refugees across borders. Although there have been no details on whether Afghanistan will send a delegation to the COP26, it remains a global obligation for all countries to assert the significance of climate mitigation policies in the country and to provide relevant funds to the state to avoid it becoming an opium-producing hub once again.

Many are already expecting another round of conflict, and this time it would be a conflict over resources, with hard-hitting poverty once more capable of urging poor people to join insurgent groups that vow to fill the void. As DW quoted Oli Brown, “War is development in reverse,” and unfortunately Afghanistan will continue to spiral down if the menace of climate change remains unresolved simply because the world refused to stand by thousands of distressed Afghans. Environmental dystopia is not just a movie genre, but for many, it is their inescapable reality.

Read More: Why is Pakistan leaning towards the Dragonbear synergy?